BY: CAITLIN VAUGHN CARLOS

On January 30, 1969, The Beatles performed their first live concert together in almost two and a half years, in an unannounced rooftop performance on top of the London headquarters of their record label, Apple Records. In a twist of irony, this first live performance would also be their last. Memorialized through the Let It Be album and documentary film (both 1970), the concert represents a mirror looking back to the roots of this quartet of rock and roll fans who had, over the course of a single decade, revolutionized the landscape of what rock and roll could mean.

But despite these significant landmarks of finality, the Let It Be recordings were not actually the last tracks written, recorded and produced by the band. That honor lies in the tracks of Abbey Road – the band’s penultimate release but final recordings. In terms of technology and production, the album embraces a more modern sound than much of their previous work, and yet so much of the song writing looks to a past time, from the 1950’s inspired “Oh! Darling” to the music hall theatricality of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Further, personally tender ballads sprinkled throughout the album – even as fragments within the famed “Medley” from the album’s second side – offer a hint of nostalgic longing, as the band closes their career together. A self-conscious swan song and a reflection of everything that had come before, Abbey Road is both inventive and nostalgically sentimental. If Let It Be is the Beatle’s return-to-roots, live-performance inspired album, then Abbey Road is the return to the studio – a look back to the futuristic imaginings and the artistic ambition that had characterized most of the Beatle’s late sixties albums, as well as the eclecticism that had pervaded their entire history as a band.

Finding Abbey Road in the eclecticism of the early recordings

Let us first situate the album in its historical context, at the crest of rock modernism and looking towards the eclectic and nostalgic rock that would emerge in the early seventies. Viewing this moment as a key departure from the hyper-progressive, “white heat” revolution promised by British leaders in the sixties, we can see hints of the disillusionment and tentative longing that can be found in a year or two later in that major works of early seventies rock – in back to roots, country rock and fifties revivals (even John Lennon’s 1975 solo record, Rock ‘n’ Roll, would take this giant of rock’s evolution back to his rhythm and blues roots). In Abbey Road, we find a Beatles’ album that is self-reflective on all that has occurred and has been created, both culturally and musically, in the previous decade. Simultaneously, the album embraces the newest recording technologies and production techniques of its time. This was the Beatle’s most modern sounding album.

Both England and the United States, at the end of the sixties, had seen a tumultuous and complicated decade. The Beatles, like the rest of the baby boomer generation, had grown up amid a soundtrack of early rock and roll. Rebellion, change and innovation was built into their understanding of self and society. In his study, Baby Boomer Rock ‘n’ Roll Fans: The Music Never Ends, Kotarba argues that rock and roll is a “primary source of everyday meanings for the first generation that was raised on it.” The boomer generation did not invent rock and roll, but they were the first generation to grow up with it. Rock and Roll, as a hybrid style, crossed the color line and challenged the adult generation of the fifties with its focus on topics favored by the youth, and deemed inappropriate for them. As Linda Martin and Kerry Segrave explain:

With its black roots, its earthy, Sexual or rebellious lyrics, and its exuberant acceptance by youth, rock and roll has long been under attack by the establishment world of adults. No other form of culture, and its artists, has met with such extensive hostility. The music has been damned as a corrupter of morals, as an instigator of juvenile delinquency and violence. Denounced as a communist plot, perceived as a symbol of Western decadence, it has been fulminated against by the left, the right, the center, the establishment, rock musicians themselves, doctors, clergy, journalists, politicians, and “good” musicians.

When these four teenagers from Liverpool picked up their instruments in the late fifties to add their voices to the rock and roll soundscape, they participated in this act of rebellion.

Further, while on the surface, the band’s early recordings seem to be simple early rock and roll tunes, in actuality, they were a complex amalgamation of rhythm and blues, skiffle (a form of British folk music that combined blues and jazz with folk or country instrumentation), and American popular music influences. While one of the first known recordings of the band (when Lennon, McCartney and Harrison were performing as the Quarrymen) is a cover of Buddy Holly’s classic “That’ll Be the Day,” performed in an almost-identical style as their idol, tracing the Beatle’s earliest recordings reveals a the wide range of American popular music influences, beyond mainstream rock and roll:

The tapes [recordings from BBC radio broadcasts in the early sixties] feature four Elvis Presley covers, including McCartney performing a close copy of “That’s All Right (Mama),” and nine Chuck Berry covers, including Lennon singing the lyrically sophisticated “Memphis.” Among the other first-wave rockers, Little Richard and Carl Perkins are also represented multiple times. That band also shows an appreciate for Leiber and Stoller’s Coasters records, as well as Phil Spector’s “To Know Him is to Love Him.” The first Anthology CD sets, released in 1995, provides five selections from the bands audition tape for Decca (including two Coasters tunes) and an excerpt from Ray Charles’ “Hallelujah I Love Her So” recorded at the Cavern Club. Finally, their first two British albums, Please Please Me and With the Beatles (both 1963), contain several cover versions, including girl-group numbers (“Chains” and “Baby It’s You”), Motown tracks (“You Really Got a Hold on Me,” “Please Mr. Postman,” and “Money”), and a movie theme (“A Taste of Honey”).

So, while The Beatles were certainly students of early rock and roll, from their earliest recordings it is clear that they were also devoted followers of all the innovations of American popular music – from song writing, to vocal harmonies and instrumentation to record production. When the Beatles return to Abbey Road studios in 1969 to record their final tracks, it is fitting that the resulting album is also an eclectic compilation of their complex and innovative sound worlds.

Abbey Road as Nostalgic Modernism

When the Beatles entered Abbey Road studios in the fall of 1962 to make their first recordings with George Martin, they were, as we have found, well versed in the latest sounds and recordings of American popular music. When they finished their recording career in the same studio in 1969, the Beatles returned to eclectic songwriting and the latest technological innovations to create their final swan song. Abbey Road was the first album where the Beatles used the Modern EMI designed TG12345 Solid State console. Previously, their albums had been recorded through valve/tube consoles. A 1969 article in Oz magazine highlights Abbey Road as both a homecoming and a step forward in recording progress:

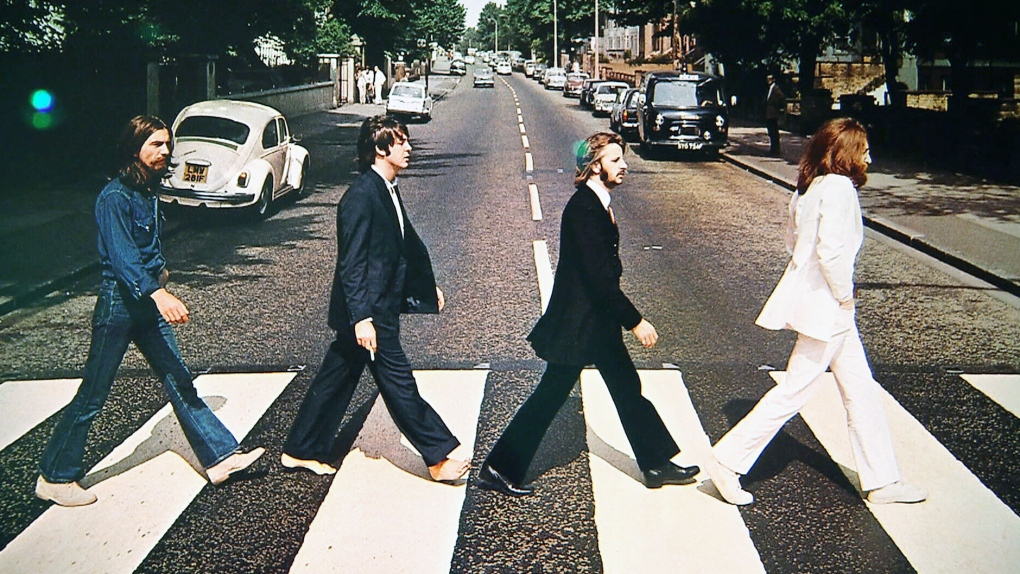

The sleeve photographs by lain Macmillan, who did their first album sleeve, represent this album perfectly. The picture shows the Beatles happily back at the EMI Abbey Road studios, after a brief flirtation with Kingsway and Trident studios they’ve gone home to where Rubber Soul and Sgt Pepper were made on old 4-track equipment. Now EMI has 8 tracks and The Beatles usual engineer, one of the world’s best, Geoff Emerick is there and so is (Big) George Martin and all… It’s like a British Carry On film, Abbey Road itself with gentle trees and late Victorian mansions, the studios Battle of Britain modern. All under a blue sky.

The Beatles are not only home physically, but at home in the space of innovation and progress. While Let it Be takes the band and their listeners back to the space of live performance and rock and roll nostalgia, it captures only a portion of the band’s musical career. They had certainly cut their teeth on exhausting tours and late night live performance gigs in Hamburg and Liverpool, but the band ultimately established their identity in the studio.

While the upgrades to EMI’s studio technology may have been behind-the-scenes alterations for the album’s listeners, there is no doubt that the album sounded different. Music critics across the board commenting on this change – whether they like the album or not. In his review of the album for Rolling Stone in November 1969, Ed Ward criticized the pieces of the album’s now-famous medley as “so heavily overproduced, that they are hard to listen to.” Albert Goldman wrote in Life magazine, that the medley “seems symbolic of the Beatle’s latest phase, which might be described as the round-the-clock production of disposable music effects.” Even William Mann, who praised the album in his December 1969 review in the Times, acknowledged that “the stereo recording will be called gimmicky by people who want a record to sound exactly like live performance” but concluded that “the stereo manipulation is used for musical purpose, not just to sound ravey.” 50 years later, Kenneth Womack explains the strikin sonic newness of the album:

The sound of the Beatles that had thrilled the world – the “maximum volume” that their producer George Martin had coaxed out of EMI’s aging studio gear – had been conspicuously altered by the subatomic properties inherent in solid-state electronics. For workaday fans and seasoned audiophiles alike – who likely had little, if any working knowledge about the equipment upgrades at EMI Studios – the sonic differences were palpable. As far as they were concerned, the sound of the Fab Four had been – somehow –irrevocably changed.

The sonic space of the album places Abbey Road at the furthest most edge of late sixties rock modernism. Even in moments when songs or lyrics look back to the past, the sound of the album to 1969 ears could only be heard as representative of the future.

In addition to the progressive possibilities afforded by the newest recording technologies available in Abbey Road studios in 1969, The Beatles also held the advantage of moving from a primary songwriting duo to four different songwriters with their own distinctive sounds. As John Lennon explained to Oz in a 1969 interview, “whenever we all combine and do it, that’s what we term Beatle music.”

Further expanding this definition and the lack of “group direction”, Lennon explains: “But we never did [have a group direction]! It was just whosever was pushing the limits at the time. I mean, we often all pushed at the same point, but it was never ‘This is the way we are going!’ As far as we’re concerned this album is more Beatley than the Beatles double album…”

When we listen to the individual tracks of Abbey Road, we can hear the tension between The Beatles’ role as the vanguard of rock modernism, and the nostalgic sentimentality of a band at the end of their career together. Although several interviews with the band at the time of its recording and release indicate the assumption that they would continue working as a band, even if they took on solo projects, there is certainly every indication that the members of the band knew that “The Beatles” as a unit, was changing (even if they did not know how that change would manifest).

Come Together

According to an interview with George Harrison shortly after the album’s release, “Come Together” was one of the last tracks to be recorded for the album, even though it is placed as the album’s opening track. The title phrase came from John Lennon’s attempt to write a campaign song for Timothy Leary in his ill-fated attempt to run for governor of California in 1969. The song, however, evolved into its own creation – a “funky bit of rock,” according to Lennon. Aside from the original inspiration, the track is notable for its heavy rock and roll feel, the type of writing Lennon would return to on his overtly nostalgic 1975 solo album Rock ‘N’ Roll. In 1980, Lennon still reflected positively on the track: “Come Together is me – writing obscurely around an old Chuck Berry thing. […] it’s one of my favorite Beatle tracks, or, one of my favorite Lennon tracks, let’s say that. It’s funk, its bluesy, and I’m singing it pretty well. I like the sound of the record. You can dance to it. I’ll buy it!”

Something

George Harrison wrote “Something” when the band was still recording the tracks for Let it Be, but hadn’t finished the song’s lyrics. He gave the song to Joe Cocker to record before knowing that it would be included on Abbey Road. It is also notable for being the first Harrison composition to place as the A-side of a single. Shortly after the album’s release, Harrison acknowledge that while he had originally envisioned it having a Ray Charles feel to the track, he was pleased with the recording for Abbey Road describing the melody as “probably the nicest melody I’ve every written.” Many artists have later performed or recorded it, including Frank Sinatra, who described it as “one of the best love songs I believe to have been written in 50, 100 years.” However, the crowning achievement, according to musicologist Kenneth Womack is Harrison’s guitar solo on the Abbey Road recording. In his 2002 list of the top 10 Beatles Moments, he names the guitar solo on “Something” as number 8, writing:

For much of the song, Harrison’s soaring guitar – his musical trademark – dances in counterpoint with McCartney’s jazzy, melodic bass, weaving an exquisite musical tapestry as “Something” meanders towards the most unforgettable of Harrison’s guitar solos, the song’s greatest lyrical feature – even more lyrical, interestingly enough, than the lyrics themselves. A masterpiece in simplicity, Harrison’s solo reaches towards the sublime, wrestles with it in a bouquet of downward syncopation, and hoists it yet again in a moment of supreme grace.

Although, as a single, the song topped out at number 4 on the charts (likely due to the fact that it was the first Beatles single to be released after already appearing on an album – and a very successful album, at that), the song has enjoyed a legacy as one of the Beatles’ most beloved songs.

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” finds its roots in one of the band’s travels to India in 1968, where both McCartney and Lennon, through their tutelage under Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, found a shared belief in a philosophy “instant karma” for those who commit a wrongdoing. McCartney described the song saying: “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” was my analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as it so often does, as I was beginning to find out at that time in my life. I wanted something symbolic of that, so to me it was some fictitious character called Maxwell with a silver hammer. I don’t know why it was silver, it just sounded better than “Maxwell’s Hammer.” The song was considered for inclusion on the Get Back / Let it Be album but became a place of tension and frustration as they struggled to find the appropriate arrangement and instrumentation for the song. It was in the middle of work recording this song that Harrison briefly quit the band during those session. However, the conception of striking an anvil or piece of iron during the lines “bang, bang, Maxwell’s silver hammer” comes from these sessions, although the final version came from the Abbey Road sessions, with Ringo hitting a real anvil rented from a theatrical agency.

When the band returned to the song in the Abbey Road session, it was the first track worked on following Lennon and Ono’s July 1969 car accident in Scotland. Still, the song took an enormous amount of time to finish, including McCartney experimenting with and recording on the Moog synthesizer for the first time. After the album’s release, Harrison described the song as “ just something of Paul’s. We spent a hell of a lot of time recording this one. It’s one of those instant, whistle along tunes which some people will hate and others will love. It’s like ‘Honey Pie,’ a fun sort of song, but probably sick as well because the guy keeps killing everyone.”

The song captures the tension between technological progress and temporal reflection. Its reference to previous songs and musical timbres of British brass band music and music hall theatricality look to the past, while the innovative use of recording technology and the Moog offers a sonic space that is undoubtedly modern.

Oh! Darling

Another one of McCartney’s compositions, “Oh! Darling” looks back to the fifties rock and roll vibe. Harrison viewed it as “a typical 1955 song which thousands of groups used to make – the Moonglows, the Paragons, the Shells and so on.” In the midst of a fifties swing and some appropriate “oohs” and “ahhs” in the background vocal tracks by the rest of the band, McCartney’s raw vocal shoutings capture some of the rebellious intensity of rock and roll at its emergence in the fifties. Audio engineer Alan Parsons recalls McCartney’s unorthodox method of trying to produce the right sound by coming in to the studio alone each afternoon to record the lead vocal track: “He only tried it once per day, I suppose he wanted to capture a certain rawness which could only be done once before the voice changed. I remember him saying, ‘five years ago I could have done this in a flash,’ referring, I supposed, to the days of ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Kansas City.’” The irony of weeks of individual takes of one vocal track to make it sound like the raw, rock and roll performances of McCartney’s youth highlights the detailed production values and artistry that went in to creating a sound that evokes a sense of the past. In order to sound unrehearsed and “live,” he had to do the opposite, relying on studio technology’s ability to record several versions of a single track.

Octopus’s Garden

“Octopus’s Garden” holds a unique place as one of only two compositions written by Ringo Starr for the Beatles. A lively, almost-childlike song, “Octopus’s Garden” takes the penultimate place on side one of the album. The song’s roots come from a moment of escape to the Mediterranean after getting fed up with his bandmates while recording The Beatles (the White Album) in 1968. Lounging on Peter Seller’s yacht, he heard the captain speaking about octopuses hiding out in the caves, coming out to find “shiny stones and tin cans and bottles to put in front of their cave.” He recalls connecting that image to his own moment of frustration, thinking “’How fabulous!’…’cause at the time I just wanted to be under the sea, too. I wanted to get out of it for a while.” While the band won him back with a telegram declaring, “You’re the best rock ‘n’ roll drummer in the world. Come on home, we love you,” the impromptu vacation inspired this charming and surprisingly sincere composition.

With Starr sitting in the same room listening and smiling, Harrison told a reporter after the album’s release, “Ringo gets very bored playing the drums, so at home he plays the piano. But knows about three chords. And he knows about the same on guitar…It’s [“Octopus’s Garden”] a really great song. On the surface, it’s a daft kids’ song, but I find the lyrics very meaningful…it makes me realize that when you get deep into your consciousness its very peaceful.” Although it didn’t fit into the back to roots rock and roll tracks of Let it Be, the song’s inclusion on Abbey Road looks back at playful, almost whimsical, side of the Beatle’s oeuvre.

I Want You (She’s So Heavy)

Another heavy blues-based Lennon composition, “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” was originally recorded by the band during the Get Back / Let it Be sessions and included Billy Preston on keyboards. It’s another example of the band turning to their rock and roll roots as their career as a unit was coming to a close. In that original jam session, they also improvised their way through two Buddy Holly singles “Not Fade Away” and “Mailman, Bring Me No Tears,” and Consuelo Velásquez’s “Bésame Mucho.” While the Holly tunes are obvious connections to the band’s early gigging career playing clubs in Hamburg and Liverpool, the Velásquez looks to an even more career defining moment in their past – their first recording session at Abbey Road studios on June 6, 1962. So while “I Want You” was still a relatively new composition when they brought it back for the Abbey Road recordings, it had been forged in the fires of their collective memory and sonic history.

As the song’s harmonic core looks to the past, the final arrangement looks to the future. At almost 8 minutes, it is one of the band’s longest tracks. Further, the album’s final master of the track is made from a compilation of previous recordings of the song with the newest innovations on the composition from the Abbey Road sessions (including more use of the Moog synthesizer). Finally, the song’s ending, with its long and powerful build up of noise and sonic effects over a rising blues progression abruptly ends with silence in an avante-guard style ending for the album’s first side.

Here Comes the Sun

Opening up the album’s second side, “Here Comes the Sun” is Harrison’s second songwriting credit on the album. Like “Something,” it has lived on as one of the Beatle’s most beloved songs. It offers both a sense of optimism and reflection at a time when the band had already faced so much tension (indeed, both Starr and Harrison had quit the band for a time during the recording sessions for The Beatles (White Album) and Get Back / Let it Be, respectively). The song’s title and chorus comes from a line in the lyrics for “Sun King,” already recorded during the Get Back sessions in 1969, but it wouldn’t be heard by audiences until the final medley of Abbey Road. However, it wasn’t until a visit to Eric Clapton’s country estate, Hurtwood Edge, later that year, that Harrison would bring the idea to life. Clapton later reminisced watching Harrison’s composition come alive: “It was a beautiful spring morning, and we were sitting at the top of a big field at the bottom of the garden…we had our guitars and were just strumming away when he started singing ‘de da de de, its been a long cold lonely winter,’ and bit by bit he fleshed it out, until it was time for lunch.”

In many ways “Here Comes the Sun” is a clear representation of the thin line between progress and reflection, around which the band continually dances in the Abbey Road recordings. Its simplicity of lyrical imagery relies on a long history of symbolism in nature and seasons in poetry and song. In addition to references to the “Sun King” recording (in the past for the band and the future for audiences), Womack points out that the chorus likely turned to the Diamond’s 1957 do-wop hit “Little Darling” for inspiration. And yet the song is modern, not only in its use of recording technology but also in its complex time signatures moving in rapid succession. George Martin heard the song as progressively inventive, saying “I think there was a great deal of invention…I mean, George’s ‘Here Comes the Sun’ was the first time he’d really come through with a brilliant composition, and musical ideas, you know, the multiple odd rhythms that came through. They really became commercial for the first time on that one.” Further, Harrison’s performance on the Moog synthesizer, and in particular, on the ribbon controller, presented some of the most modern sounds 1969 had to offer.

Because

One of John Lennon’s contributions, “Because” was the last song recorded for the album. Like many of the previous songs heard on Abbey Road, we can find aspects of both modernist imaginings and nostalgic reflection in this track. One of the song’s most powerful sonic features is the lush three-part harmony. It seems unusual in the context of this album, but as musicologist Elizabeth Randell Upton points out, the band had been recording in a wide range of complex vocal textures throughout their career. In looking back through the band’s recorded history (especially the covers on their early albums) and, in particular, noting which songs become highlighted in films (such as Help!), Upton also suggests that 3-voiced harmonies – like those found on “Because” – may actually be understood as one of the band’s early defining sonic features. However, the vocal harmonies on “Because” were significantly more challenging than their previous experiences with that vocal texture. George Harrison called the song “one of the most beautiful things we’ve ever done,” but admitted that “the harmony was very difficult to do, we had to really learn it.” Characteristic of the Abbey Road recordings in general, the homecoming found in “Because” is not a simple back-to-roots return to rock and roll, but rather a return to the innovative complexity and creativity that had characterized their entire career.

fFurther, the sonic space created by the song is of particular note because of how it sets up the transition between individual songs to a more avante-garde conception of musical creation in rock with the album’s elaborate final medley. As Upton explains, the “floating harmonies change the mood of the album…to one of timelessness, signaling to the listener that what will follow will also be special.”

The Medley

Along with Harrison’s guitar solo on “Something,” Womack declares the final medley on Abbey Road as one of his “Ten Great Beatles Moments.” Essentially, a “medley of Paul and John songs all shoved together,” the final track of Abbey Road often looks to the past both lyrically and in the weaving together of bits of songs from several different moments in the band’s past. Some (like “Sun King” and “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window”) had been part of the Get Back / Let it Be sessions, while others (like “Mean Mr. Mustard”) had been contemplated for The Beatles (White Album) back in 1968. “Mean Mr. Mustard” finds its roots even further in the past – originating in the band’s internal repertoire during a 1968 trip to India. Lyrically, “You Never Give Me Your Money” reflects on the financial confusions and troubles that had plagued the band throughout their rise to stardom, McCartney later recalled “We used to ask ‘Am I a millionaire yet?’ and they used to say cryptic things like, ‘On paper you are.’ And we’d say, ‘Well, what does that mean? Am I or aren’t I? Are there more than a million of those green things in my bank yet?’ and they’d say, ‘Well, it’s not actually in the bank. We think you are [a millionaire].’ It was actually very difficult to get anything out of these people, and the accountants never made you feel successful.” By the end of the sixties, and their career, their financial entanglements had become even more tension filled and frustrating. While “You Never Give Me Your Money” looks to the band’s career-long troubles with financial clarity, “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” references a specific moment in McCartney’s life – a 1968 burglary of his Cavendish Avenue home by several of the female fans who would often wait outside locations frequented by McCartney and the band. “Polythene Pam” looks back even further – to the band’s gigging days at the Cavern Club with a vaguely hidden reference to a club regular named Pat Dawson, to whom they had given the song’s title as a nickname.

And yet the band takes of all this lyrical and sonic reflection of their past and transforms it into modern rock artistry. George Martin had been encouraging the band to record a “pop opera,” and in fact, while the Beatles were recording “You Never Give Me Your Money,” the Who released their rock opera – Tommy. The Beatles were not interested in following suit, but they retained an interest in working in a large-scale form. The resulting montage negotiates the space between the band’s avant-garde creative tendencies that characterize their later sixties works and a reflection upon the entire past decade that seemed to hover over all of their final attempts at recording together.

Abbey Road – Fifty Years Later

Although it was released before the Let It Be LP, the recording sessions for Abbey Road represent the final days of creative music making for the Beatles. The album becomes a time capsule of the progressive creativity of artists at the top of their game, while simultaneously reflecting on a decade of writing, performing and recording music together. As we have seen, the juxtaposition of modernity and pastness characterize both the individual tracks and the album as a whole. For its time, Abbey Road was undoubtedly modern, sonically, while so much of the songwriting and lyrics look to the band’s past. The homecoming of the Beatles’ return to Abbey Road studios in 1969 to record their final tracks is perhaps so meaningful because it marks not only the band’s final days, but also the conclusion of the entire sixties’ dream of progress and revolution. As the decade ended, the seventies emerged as nostalgic age, surrounded by fifties revivals (i.e. American Graffiti, Grease), country-rock/Westerns and medievalism. But in 1969, even nostalgic reflection was expressed through progressive and revolutionary creativity.

Today, we look back on Abbey Road as a nexus of hope and memory. The album’s progressive features have become markers of cultural meaning for a 21th century world. We experience Abbey Road both as personal nostalgia and cultural memory. We may no longer be surprised by the changing meters of “Here Comes the Sun,” but we vividly remember moments in our lives to which the song provided the soundtrack. Abbey Road Studios and its famed crosswalk has, because of the Abbey Road album, become a tourist landmark – a physical marker of cultural meaning that we all can share. 50 years after its release, Abbey Road continues to hold a sentimental place in the public’s cultural and musical memory.