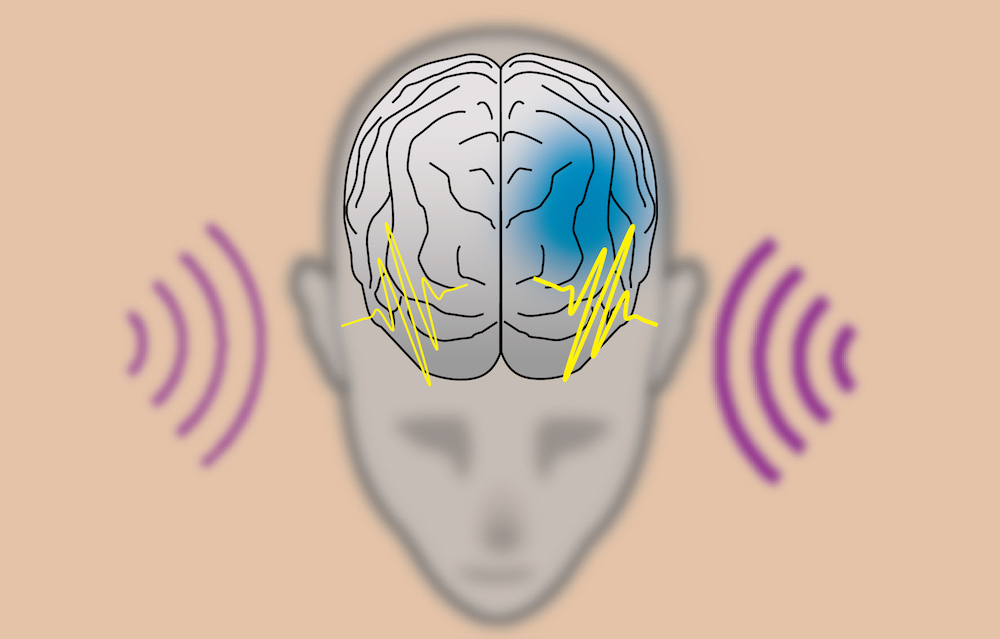

The Haas effect is a psychoacoustic phenomenon discovered by Dr. Helmut Haas in 1949. Also known as the “precedence effect,” the law states that when one sound is followed by another with a delay time of approximately 40 ms or less (below humans’ echo threshold), the two are perceived as a single sound.

This relates to how we determine spatial location by sound. Because two noises with a very short delay between them are perceived as one, spatial location is determined by the first heard, dominant sound–regardless of where the second came.

To summarize, we determine the source of a sound based on what arrives at our ears first. Any subsequent reflections or noises arriving after a short delay give the sense of depth and spaciousness and do not appear to be individual sounds.

The Haas Effect in Audio

If you’re looking for interesting tricks to add to your mixing arsenal, something to experiment with is taking advantage of the Haas effect. As we’ve noted above, very short delay times that make up the Haas effect create spaciousness, while longer delays give us distinct repeats and a greater sense of directionality.

Generally speaking, we rely heavily on panning to give directionality to our mixes. But whereas pan pots control the volume going to each channel, using delay, of course, controls the timing of each channel. As humans, we rely on both intensity and timing to perceive sound, so capitalizing on the Haas effect can yield some pretty fantastic results. Here’s a neat trick:

How-To: A Mixing Trick Which Uses the Haas Effect

This is one method of using the Haas effect to create a wider stereo image, which lends itself to a broader mix with more depth. Start by duplicating a mono audio track and pan each of them hard left and hard right. Then, simply add a short delay to one of the tracks.

Where you set your delay time yields different results, so it’s best try things out until you find something that sounds good to your ears. Remember, though, that the goal here is to make our identical mono tracks sound wider than they really are.

A delay of somewhere around 5 ms on one track will actually enhance directionality and yield an “out-of-phase” type sound, which isn’t what we’re after. For example, if you’ve delayed the left-panned channel by 5 ms, the sound will appear more intense in the right-panned channel.

Up to a certain point, the more delay you add will further enhance directionality. However, once you’ve surpassed say, 10 ms or so, your two tracks will sound wider rather than more or less intense in one channel.

The trick is to keep the delay time below our ears’ echo threshold–approximately 35-40 ms for most people–so that no distinct repeats are audible. You’ll find that you’ve widened the stereo image of, and added dimension to, an otherwise “flat” mono track, without reverb or an imaging plugin!

Other Uses of Psychoacoustics in Mixing

Using the same technique above, you can also reduce directional masking in your mix. When panning doesn’t cut it, we have to rely on the timing component of our hearing to cleverly maneuver throughout the stereo field. You can try using a stereo delay with one channel set to 0 ms while tweaking the other side to taste.

Using the Haas effect’s principles, we can also “thicken” mix elements using the early reflections from a reverb plugin. Because early reflections typical occur well under the 35-40 ms echo threshold of our ears, they’re also within range of the Haas effect.

Forget the notion that reverb tends to push elements into the dark recesses of the mix abyss. Without using the reverb tail and only using early reflections, you can thicken up the initial transients of a sound for a beefier, in-your-face attack.

Get Mixing!

Now that you’re more familiar with the Haas effects and it’s usage in mixing, you can start to experiment with these techniques in your work!

Remember, you can utilize the psychoacoustic phenomenon in several ways with distinct results. To make a wider, deeper stereo image, duplicate a mono track and pan each hard left and hard right. Delay one channel somewhere between 10 to 35 ms, and you will have enhanced your stereo imaging! The same technique can be applied to reduce directional masking when panning doesn’t get the job done, too.

Finally, by using the early reflections of reverbs that fall within the Haas effect’s range, you can thicken up the transients of mix elements for more attack and aggression.