Science tells us that people prefer their music loud. As sounds get louder and louder, their overall frequency curve begin to flatten out, so you can more easily hear the whole “picture.” The “louder is better” philosophy usually begins with artists and producers in the studio, until audiences come to expect in-your-face products all the time. This is the basis of the loudness war — an evolving trend of making songs as loud as possible.

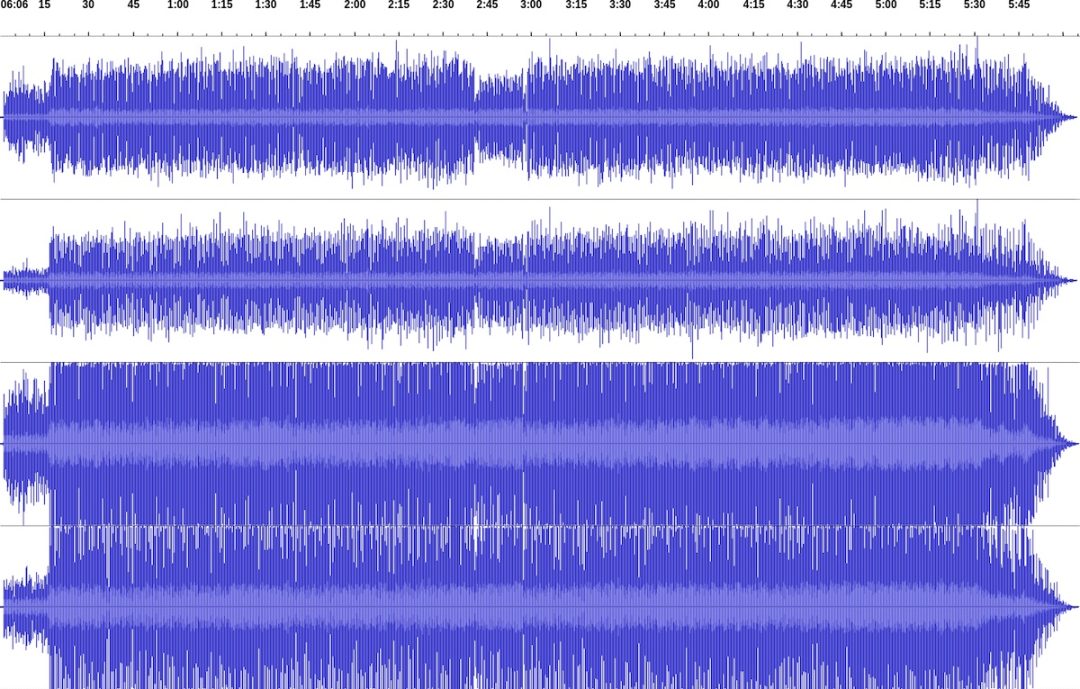

Featured Image: Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough” — 1983 vs. 2001.

What Is the Loudness War?

The loudness war is essentially a competitive mindset driven by the idea that a if your song is louder than someone else’s, it’s also better. The artist is going to prefer it, consumers are going to prefer it, and as long as a master is loud, it’s also good.

The main culprit in mixing and mastering techniques is the abuse of limiting in an effort to increase volume. Critics of the loudness war assert that modern productions favor volume over quality; and further, that these productions hold little regard for fidelity in an effort to please the masses.

Is Music Really “Louder” Nowadays?

Music is definitely louder. From the early ’80s until the mid 2000s, there was a steady increase in overall level. On average, today’s music sits at around 5 dB louder than music from the 1970s, for example — if not louder than that.

With regard to more concrete numbers, the RMS level of a typical rock song in the 1980s sat at around -17 dBFS. CDs weren’t the norm until the latter part of the decade, so loudness wasn’t the war it would become just yet.

Fast forward to 1995, in which Oasis’s (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? shattered those numbers and became a benchmark for loudness, with most songs on the album hitting around -8 dBFS. And it seemingly went onwards and upwards from there. The Red Hot Chili Peppers’s Californication, released in 1999, actually clips because it’s so loud. (citation)

How Did The Loudness Wars Begin?

The origins can be traced all the way back to the days of 45s. Producers would often request their single be cut hot, so that it would stand out to a radio station director and hopefully get into the play rotation. As a physical medium, there were limitations to how big the grooves could be cut, and ultimately how loud the song could be. Something that disappeared with the advent of CDs and digital recording.

At first, engineers were cautious of the 0 dBFS ceiling in digital recording for CDs. That’s shown by the average ’80s rock song sitting at a modest -17 dBFS. Eventually, however, the preference for loudness gradually took precedence in the 1990s. Engineers starting using different techniques to make their records louder and more competitive than the other person’s. Digital plugins like the Waves L1 limiter, released in 1994, played a major role.

Part of the shift towards louder music came from consumer products, like CD changers, as well. No producer wanted their album to be perceived as the “quiet” one in a rotation; thus, the average level of CD masters crept up and up. Still, at this point, the loudness war wasn’t as explicit as it became in the early and late 2000s.

Digital Compression and Dynamic Range

Heavy-handed compression and limiting are the primary means of increasing loudness. Both of these reduce the dynamic range of source material by making the quiet parts louder and louder parts just a bit quieter. You end up with a waveform that looks almost the same shape the whole way through.

But there’s also digital compression, which is the process of shrinking large WAV files into MP3s so they take up less space (and cost less streaming bandwidth). In an effort to reduce file size, MP3 encoding prioritizes the quiet bits of a song to retain more information; but the loud parts, where subtlety and detail in the song is less noticeable, are given less information because encoding errors are masked by the overall volume.

- SEE ALSO: Types of Audio Compressors and Their Uses

- SEE ALSO: What is Audio Bit Depth?

How This Signal Processing Affects the Overall Sound of the Songs

At best, over-compressed music is fatiguing for listeners. It smears details, everything is right up in your face—Bob Dylan has gone so far as to describe albums, who fell victim to the loudness war, as “static.” All of the nuance of a great recording is sacrificed for loudness. Fidelity as a whole decreases.

At worst, albums competing for volume sound clipped and distorted; a once hi-fi recording goes down the tube for the sake of volume. Loud (pun intended) critics of the war over the years include industry legends like Alan Parsons, Geoff Emerick, Doug Sax, and Bob Katz. Despite this, fellow legend Rick Rubin is known for perpetuating the loudness war, namely with Californication and Death Magnetic.

The Curious Case of Metallica and Death Magnetic

2008’s Death Magnetic is the most well known example of what the loudness war has done to music. The album was so hopelessly over-compressed and limited that it just sounded terrible. Critics and the average consumer alike recognized how poor the sound quality was.

In some sense, Metallica and Rick Rubin won the war. Ultimately, people began realizing just how awful loudness-for-the-sake-of-loudness could be. Funnily enough, Guitar Hero III featured tracks from Death Magnetic in their uncompressed, multitrack form. Players of the game noticed that the songs actually sounded great compared to the studio version. It was the beginning of the end of the loudness war.

Is the Loudness War Still Going on?

Not really, and we have digital music players (iPods, etc.) and streaming services to thank. Both incorporate loudness normalization in their playback formulas, so overly loud music just gets turned down compared to the quieter tracks. When that happens, most listeners realize the lack of depth on tracks that came in way too hot. Normally mixed/mastered material, with deference to dynamic range and openness, tends to be preferable.

Key Takeaways from the War

Today, the vast majority of music is consumed via streaming platforms. Loudness normalization varies by platform, but Apple Music, for instance sets their peak at -16 dBLUFS. They’ll just turn down any material coming in that’s louder than that.

The hopeful outcome of this is that mixing and mastering engineers will go back to focusing on dynamic range, depth, and interest as opposed to straight-up loudness. Even creative use of saturation and appropriate compression can increase perceived loudness without squashing a mix with a brick wall limiter. Only time will continue to tell.